“We never tried to wake our children up on weekends: the more they sleep, the less they eat.”

-Natalia

Recently, the Russian-speaking segment of the Internet got flooded with personal photographs from the 1990s. I first took note of them on my own Facebook feed. Some appeared expectedly funny—imagine the hairstyles!—others were nostalgic. Yet what seemed like a spontaneous flashmob turned out to be a planned event. In fact, this social-networking experiment was organized by the Yeltsin Foundation in conjunction with one opposition publication. It targeted the under-40 demographic, but especially those born in the late 1980s-early 1990s, who were too young to remember some of the horrors of that decade. Thus, the purpose of this pseudo-spontaneous photo-sharing was to reshape the memory of a nation about the early years following Soviet collapse. This memory has been overwhelmingly negative: looting the country’s natural resources by the select few, mob violence in the streets, daily hunger, institutional collapse, and national humiliation, just to name a few aspects.

And now, a new Yeltsin Center that includes a museum and an archive is being launched in Yekaterinburg, Russia on November 25 by the same non-government organization. Its declared purpose is the seemingly benign preservation and analysis of the social and political events in the 1990s. This upcoming opening has been accompanied by a substantial and professional social-media campaign and consequent protests.

Some of the protesters pointed out that its location in Siberia and the recent slew of visits by foreign diplomats are not coincidental, and are meant to generate social unrest and “Siberian separatism.” The latter does not actually exist on any meaningful scale, though certain Western media sources hyping it in order to serve their respective countries’ geopolitical interests certainly wish this were true. In any case, these protesters are wary of the so-called color revolutions gone wrong, and many Russians, in general, view the Center’s purpose as one of rewriting history. Whereas what happens with the Yeltsin Center remains to be seen, the photo-sharing exercise in soft power turned out to be a failure.

After all, in addition to photographs, thousands of people, including the target demographic itself, disseminated personal commentary that was less than favorable. Some of it is worth translating and appears below. I have taken these reader statements from the Facebook page of a well-known Russian journalist, Dmitrii Steshin, who writes for Komsomolskaia Pravda.

There are many interpretations of the USSR’s dissolution—from Western malevolence to a people’s utopian desire for the ideologically Liberal values of democracy and freedom, personal and economic. The truth is somewhere in between: the combination of Western pressure, failure to transform a giant ossified bureaucratic organism in dire need thereof, and the country’s own elites betraying national interests are some of the most important factors to consider.

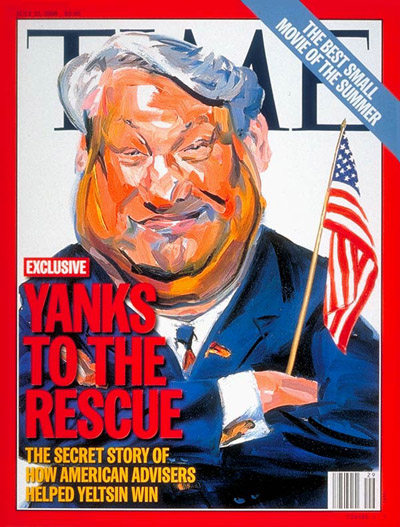

Time, July 15, 1996 issue highlights Western engineering of a fraudulent election.

After 1991, nothing was the same. Some saw this brave new world as an opportunity, but most were lost. Social guarantees, toward which many worked and contributed all their life, disappeared. Many institutions simply collapsed: well-educated and extensively-trained scientists and engineers were out in the streets, if not literally, then making too little to provide basic necessities.

Just ask my parents.

Protest signs read: “A hungry physicist is a SHAME for Russia” and “Give scientists the salaries that they are OWED.”

Factories and entire factory towns stopped operating. The military was demoralized: unilateral pullback from abroad with no written guarantees from NATO. (Look where that got us today.) Russia turned into one big open-air market with what some euphemistically described as “small business.”

Luzhniki Stadium-area of Moscow as a giant open-air market, 1997. This and most other photographs below are from an exhibition called Boris Yeltsin and His Time (Boris Eltsin i Ego Vremiia) by the Moscow House of Photography.

In truth, the more entrepreneurial residents traveled abroad to purchase clothing and other kinds of products to resell them at a markup domestically. “Export / import” turned into a joke about Eastern Europeans everywhere.

Hostages leave a Budenovsk hospital captured by a group of terrorists in 1995, the result of which was 129 dead and 415 wounded.

Thanks to the newly-opened borders, Russia was introduced to a whole new world.

Of drugs.

Budenovsk hospital at the time of the terrorist attack, 1995.

And terrorism.

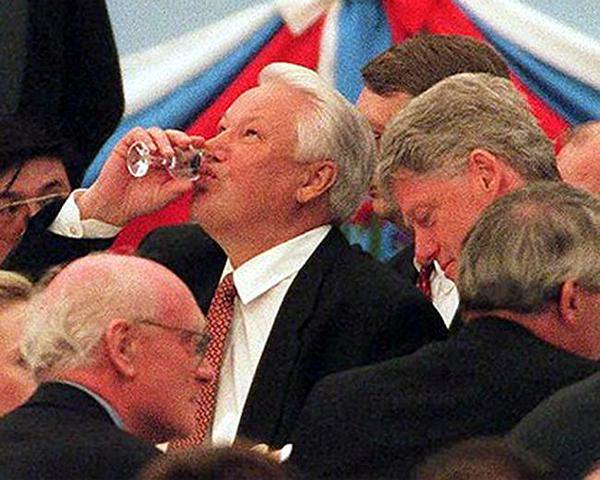

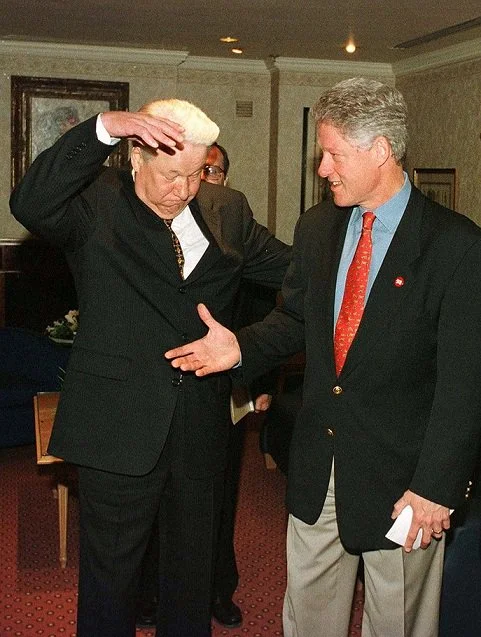

Boris and his friend, Bill.

The country’s so-called leader made a fool out of himself seemingly on schedule, whether through drunken public appearances or prancing around with that iconic sign of global capitalism, McDonald’s logo, following in the footsteps of the previous leader, who opted for Pizza Hut commercials.

Boris and his friend, Bill. Again.

Democracy was about Coke or Pepsi, after all.

![Yeltsin-McDonalds[1]](https://ninabyzantina.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/yeltsin-mcdonalds1.jpg?w=676)

Yeltsin at a McDonald’s opening, early 1990s.

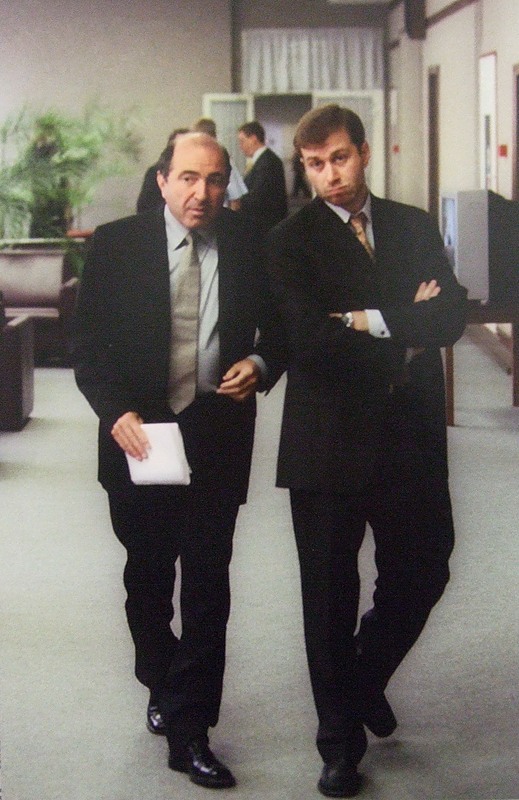

Oligarchs Berezovsky and Abramovich, 2000.

Turf wars left people gunned down in the street in broad daylight. The eXiled made fun of it all.

Most suffered.

This was the period that gave birth to one lasting expression, “If you’re so smart, then why are you so poor?”—a criticism directed towards those, who were lost in this surreal new world of wild capitalism.

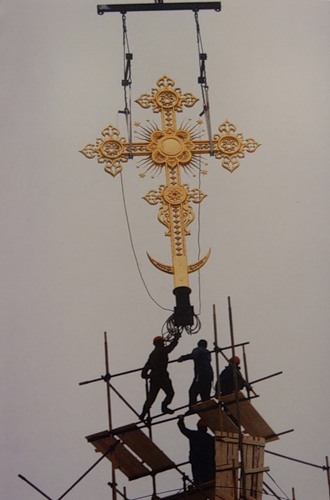

It wasn’t all bad, of course. Literature and historic writing was now free of rigid ideological constraints, though initially its pendulum swung too far in the opposite direction. Perhaps, understandably. And, they were back. Churches. Hundreds of them.

One of the smaller crosses being attached to the reconstructed Church of Christ the Savior, Moscow, 1995.

Most important was Yeltsin’s legacy of leaving Putin in power. The latter systematically “undid” the damage of the 1990s. Imperfectly. Incompletely. But his leadership provided the country with the kind of reasonable stability domestically and sovereignty internationally that his people forgot could be possible. So next time you smirk about Putin’s impressive ratings, remember the 1990s.

Misconceptions about this decade persist. A particularly pesky one is that the USSR’s collapse had been nearly bloodless. This, of course, is grossly inaccurate, and its affects are still being felt today: the Ukrainian conflict is the prime example. Transnistria, Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Tajikistan, Chechnya… Prior to the war in Donbass, estimates of those who died in military conflicts in the former USSR range from 100,000 to 600,000.

Rally in support of Georgian President Gamsakhurdia, Tbilisi, 1992.

The rest of the statistics for the 1990s show a demoralized people. Overall death rates rose from 10 per thousand in 1989 to 16 in 1994, which is considered unprecedented in peace time. Among causes of death from external reasons, suicide was at the top of the list, up to a quarter of all cases for men. Its rates, specifically, drastically increased: 41.8 per 100,000 population in 1994.

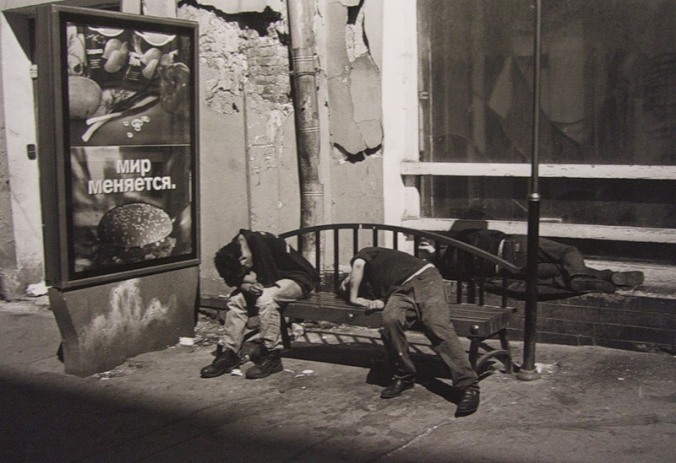

So did alcohol consumption.

Moscow, 1995. Bus-stop ad reads: “The world is changing.”

Abortions skyrocketed. Violent crime grew twofold by the early 1990s, and between 1992 and 1997, 169 thousand people were murdered. Emigration increased dramatically. People fled war and unemployment. Russia alone accepted 11 million asylum seekers between 1989 and 2002. Most of them came from the former USSR. Some commentators have suggested that the numbers of those, who died in this decade due to political and social turbulence as well as war, rivals those lost in Stalin’s 1930s.

But I’ll leave statistical calculations to professionals. In some ways, memories of those, who lived through it all, speak loudly enough.

Most comments that I’ve translated from Dmitrii Steshin’s page could be organized into three categories: food, salaries, and the spirit.

Irina recalls:

First payday without parents: a pack of kasha, vegetable oil, a pack of sugar, tea, and shampoo. Dieting! 🙂

Natalia states:

I remember one particular day from the 1990s: in the morning, really early, we went on a walk to the park with our dogs. We never tried to wake our children up on weekends: the more they sleep, the less they eat. Anyhow, we found several mushrooms in the park and returned home happy, since we had pearl barley at home and could make soup!

Foma writes:

In my town, all the pigeons were killed [and eaten]. People searched for food dumpster-diving. Shock therapy.

Svetlana describes her experiences here:

I gave birth to my son in December of 1993. That particular winter was quite cold, and our apartment building barely had any heat. When we returned home from the hospital, it was 10 C (50 F—Ed.) degrees inside, so we lived in a small room without turning off our portable heater for days.

And here:

I also remember that it was even difficult to buy soap: the stores were empty. My daddy, who was always very organized, came home one day feeling extremely pleased with himself, dragging a three-liter jar with brown stinky goo. The latter turned out to be liquid soap. We used that horrifying substance for bathing for a long time.

Evgenia responds:

This is difficult to read, brings me to tears! It’s scary to remember that to this day I’m afraid to be left alone with an empty fridge, as if I grew up in besieged Leningrad (during World War II—Ed.). To this day, I feel acute shame because I had thoughts about stealing groceries. And, yes, we had to eat food covered with mould.

Valentina remembers this:

My friend fainted from hunger making kasha for her two little children.

And this:

They also did not pay us in money, but in light bulbs, for instance. Then we had to sell the light bulbs in order to buy something to eat. Or barter.

Elena reminisces:

I was happy back then because I was in love. I also had a bag of flour and a bag of potatoes.

Roman writes emotionally:

I remember that my mom bought me a Mars chocolate bar for my birthday. Then there were no more sweets for a long time, because we ran out of money. How many died back then just like that? We can’t say anything good about anyone from that particular government. If they were still alive, we should’ve put them to the back of the wall.

Vladimir remembers:

We ate macaroni. For breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Marina says:

I don’t want to remember those years. I only recall that I came up with the following motto: “We will survive despite everything!” I grasped the fact that we have begun to live better when we got the ability to buy fruit for our children on a regular basis. I’m not talking about limes or avocados, but simply apples, pears, and oranges.

Yana recalls:

I was a college student at the beginning of the 1990s. I remember that one winter I kept having dreams about apples. 🙂 Evidently, I lacked vitamins terribly, because apples were a huge luxury for me.

Olga describes her memories:

I took my little five-year-old child (I had no one to babysit) and traveled to the nearby town (this was embarrassing to do in my own town) and sold worn children’s clothing, which my daughter outgrew. If I were lucky, then I used the money I earned to buy food. Then there was barter…

A user with a pseudonym comments:

For me, the worst thing about the 1990s was not hunger (it wasn’t that bad, by the way), but rather, the constant, tedious, and continuous sense of humiliation. Today, I would call this national humiliation, but back then…you turn on the television and see drunken Yeltsin, the first Chechen war, and the nationalists in the former Soviet republics…In the streets, there was a mixture of wild poverty and, at the same time, similarly wild tackiness. Discos, tents with booze. Maybe it wasn’t this bad in reality, but this is precisely how I remember it. I can’t even look at my photos from the 1990s: I can’t believe this is how we dressed and styled our hair!!!

Another commentator adds:

The clothing factory made a deal with the nearby macaroni factory to buy macaroni in bulk, which they then sold to us at five times the market price. It was either about taking the macaroni then or waiting for the money to appear. Macaroni for a year and a half.

Yulia remembers:

Food stamps, kasha, and macaroni with onions and carrots. What I really craved was milk products and meat. And money in the millions [due to hyperinflation]. One time, my mom caught a parrot in the park. He lived with us for a year —screaming—then we took him to a local open-air market and sold him for a million. We walked to school. It was hard to walk back because we felt dizzy [because of hunger]. They paid salaries in jackets.

Asya writes:

Every recess, I sat at my desk in school because I was exhausted from hunger. I was unable to walk or laugh. Later on, I read that this is how those, who lived in besieged Leningrad, felt. Then I stopped having my period for six months. I also stole bread and tvorog (quark—Ed.) from the grocery store a few times.

I have a few memories of my own, too. Receiving large, very elongated cans of humanitarian aid at my school with mystery meat inside. Spam, I think. It was very much expired, but we ate it.

Seemingly endless tank convoys beneath my windows, though it wasn’t a parade that they were about to visit.

August-1991 putsch, Moscow.

Pink bubble gum.

Swan Lake on television instead of the regular programming. For hours.

First dubbed tapes of German heavy metal.

Missing school that was located close to the Moscow White House, as Yeltsin shelled it during the Constitution Crisis. “Snipers on roofs,” they said. Hundreds were left dead and wounded.

And herein lies the problem, you see. A concerted effort to repackage a far-removed historic period isn’t difficult, as these Yeltsin Foundation initiatives seem to have attempted. See the way in which Western universities mold Russian history to match their own ideological reading, for instance, and the way it is then disseminated through NGOs back in Russia. This is much more difficult to do with recent, living memories shared by the majority of the people. Indeed, it is especially difficult to do when the said people are no longer experiencing historic disorientation and national humiliation of the Yeltsin era, but are, instead, certain of their past and hopeful of their future.![04-10-1993_bellabs_39[1]](https://ninabyzantina.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/04-10-1993_bellabs_391.jpg?w=500&h=388)

Thanks for your article and your translations. We definitely need more of this. I have never had the opportunity to travel to Russia, and I know from my research about Western media and academic reporting about China how important it is. But even without having travelled there, just by having a look at reliable statistical data, it is obvious that the Western academic and media discourse about Russia under Yeltsine is pure ideological propaganda.

GDP figures provided by the World Bank or the IMF and social statistics like life expectancy and homicide rate provided by UN organs perfectly match your story and the testimonies you provide. I know that World Bank and IMF policies imposed on Russia were a disaster, but at least these organizations are honest about the disastrous consequences. Then just look at what Western academics and media make of it: “a necessary economic correction”. Bullshit.

Would you agree that I republish this story on my blog http://www.rainbowbuilders.org, of course under your name with due credit and links to your article above? There are already several other articles from other contributors. I intend to write an article about the evolution of GDP and social indicators in Russia using an interactive chart tool I have developed. Otherwise, I can also just put a couple of links to your article. Maybe we can work together in order to provide some solid information about certain aspects of Russia’s past which are systematically deformed by Western academics and media.

If you are interested, you can contact me through my email address which I entered below, through facebook or through the email address you find on the contact page of my blog.

Nina, I’m an American who’s never been to Russia, but I remember the news about your country back in those days very well. I grew towards the end of Cold War I, and like most people, I basically accepted all the government/media propaganda about the USSR. At least back then, the propagandists did not attack or defame the Russian people or culture. According to them, the only problem was communism, and once that was gone, relations between our two countries could improve.

When the events of 1989-91 went down, I was elated! At last, communism was finished, and we could be friends with Russia–or at least not enemies. But over the next few years, my elation was quickly replaced with consternation and disappointment. As Russia was an advanced country with loads of the natural resources and highly trained scientists, I had anticipated that they would do very well after shedding communism. But to see a once proud, advanced people forced to dig through the trash for food was truly depressing. Back then I assumed that ‘shock therapy’ was some sort of well intentioned accident; I now know differently, of course.

Then came the Yugoslav wars, which set in motion a policy of relentless NATO expansion. Why? I wondered. Since the Warsaw Pact had already disbanded, why couldn’t we just pull out and go home? Russia was no longer a threat and Yugoslavia was none of our concern! I now know differently of course.

Then Putin became president. I didn’t think him anything remarkable at first, though he was at least sober, unlike that drunken idiot Yeltsin! But over the last 10 years, I have followed him–and Russia–as closely as I could from abroad. And precisely as my admiration for him grew, the western MSM’s campaign of vilification of him became ever shriller. In the popular media, Putin–along with Russia, her people and her culture–are mocked and disparaged. But I don’t buy a word of it! Nina, after the indignities your people suffered in the 90s, I am so glad to see things finally going right for Russia.

Right now, things are very bad in the west. These are dark times. I believe that we are living through our own ‘Brezhnev era of stagnation’ right now. But to see the turn-around that has taken place in your country at least gives me a ray of hope, and restores some of my faith in the human race. It’s not just that Russia has recovered economically to some extent, but she has also recovered her pride and self-respect.

If indeed we are now embarking on a second cold war, this time I will be for Russia. Slava Rossiya!

This is certainly the most evocative expression of the imperfect but undeniable (by any unbiased observer) progress that Russia has made since the demise of Boris Yeltsin. It is also the most elegant appeal for balance among mainstream media at a time when it has never been more desperately needed. I have just scanned your piece on the Realities of the Russian Media Landscape. It is, at first glance, an excellent analysis of what I have long seen as the American neocon-dominated pot calling the Putin kettle “black.” I would like to re-post “if You’re So Smart…” on my website, with your permission. Wonderful insight. Please accept these compliments from an older person who wishes there were more, young and old, who are beating the bushes of alternative media due to the disgraceful state of our mainstream media. It seems that we are being prepared for war – and I am ashamed of, and angry with, our own Canadian Broadcasting Corporation for its complicity. Pockets of welcome dissent can still be found among the thinkers interviewed on some of the CBC’s surviving radio treasures, such as Writers and Company, Ideas, The Sunday Edition and Tapestry. In the last couple of years I have sometimes felt as if I were in World War II Vichy-dominated Paris listening alone to some forbidden, free radio source that permits me a few gasps of precious, intellectual “oxygen.”

Let us hope that these last remaining freedoms and sources are not taken from us.

For the sake of my grandchildren…

Nina,

If you’re not a Kremlin-bot as you claim, you are one of the most interesting and articulate people I’ve discovered.

My major in college was Comparitive Literature (19th century), and I’ve had a deep and abiding interest in Russia and the Russians since.

Lately as my daughter participates in Rhythmic Gymnastics, I’ve gotten to know a lot of Russians very well and I’ve found them to be very warm and genuine for the most part.

One subject in particular that I’ve picked up rumblings about and confirmed with some of the older Russians I know is the role of the United States in encouraging, organizing and maintaining the Soviet structure and apparatus, which of course is contrary to everything we were taught in school (I’m a fifty eight year-old man from the Ameeican South).

If you have any essays or thoughts along those lines, or further reading on the subject, I would appreciate your dropping me a line and letting me know.

Thank you,

In the 21st Century, no one should have lived like this. Great comments.

@Bill Acuf: I find your barely disguised allegation that Nina might be a Kremlin-bot quite insulting, but anyway, whatever I say on this topic, it will be useless since you might also consider me to be a xxx-bot.

I am not a specialist in Russian history, but I know a little something about the attitude of the West towards the Sovjet bloc. Regarding the rumors about “the role of the United States in encouraging, organizing and maintaining the Soviet structure and apparatus”, I can only say that looks like total nonsense to me. Such rumors are perfectly in line with the numerous conspiration theories spread on some so-called “alternative media”, for example that the Paris attacks were staged by the French secret services and that actually nobody was killed.

For the US regime after World War II, the existence of a political alternative to their bi-party liberal democracy was a threat in itself, because many US citizens considered that this regime did not really represent their interests. In particular, the emphasis of the Sovjet model on social progress and the remarkable results they achieved (according to recent research by main-stream Western academics) was extremely problematic for the US elite. If any of the US administrations could have done anything to cause the Sovjet-block to break down, I have got not doubt that they would have done it. The fact is that when the opportunity came, that’s exactly what they did.

On the other hand, we should take into account that the Sovjet regime has been able to survive and even get stronger during World War II, when almost half of Europe threw all their armies against it and the rest of Europe did not much to stop them from doing it. The extent of US wartime help has always been qutie exagerated; the fact is that the Sovjet Union fought exclusively with weapons they had developed themselves and produced in their own weapons industry which they had built up well before the beginning of US wartime help.

The victory over Nazi Germany and the impressive socio-economic development which followed WWII in the Sovjet Union did not make any kind of US help necessary. You can have a look at the most reliable data provided by international organizations presented in an interactive chart on my blog;

http://www.rainbowbuilders.org/china-development/socio-economic-development

The article is about China’s development, but you get GDP and life expectancy data about the Sovjet Union / Russia. In the GDP charts, you can select any country you like to be included in the chart.

Of course there are people, including Russians, who did not like the Sovjet regime. With regards to every single political regime on earth, there are many people who don’t like it… However, finding a few people who come up with some conspirational theories is not really any kind of proof that this is true. In my experience, the only way of separating absurd bullshit from plausible theories is a multi-layered approach, mixing testimonies, serious academic research, analysis of data from international organizations, and some common sense.

It was obviously due to resource depletion