«The newspapers—going mad from all the contradictory rumors—willingly printed all this nonsense…These rumors lost their direct purpose of reporting fictitious “facts”…They turned into a means of self-soothing or a powerful narcotic medicine. Only in rumors, people found hope for the future. Even outwardly, Kiev residents began to resemble morphine addicts.»

Editor’s and Translator’s Note

Thinking about the chaos that seems to periodically erupt in the territory of Ukraine, a Hegelian would argue that there are historical inevitabilities that explain such large-scale events. A student of geopolitics would add that the relationship between land and politics backed by the knowledge of history shapes our understanding of the world. On more than one occasion, we discussed the striking parallels between the turbulent events of the early 20th-century Russian Civil War in the territory of Ukraine and the present-day conflict in the region. Yet, the following excerpt from Konstantin Paustovsky’s autobiographical The Story of a Life (1962) goes even further to shed light on mis- and disinformation, mass media, as well as the social mood in Kiev immediately after the 1917 Revolution.

After all, Paustovsky, a Nobel Prize-nominated Soviet author, spent his youth between Moscow and Kiev. While in Kiev, he documented his perceptions of the frequent changes in the self-proclaimed governments, foreign “interventions,” and the way in which the public responded to them. In this sense, his writing is valuable because it provides an additional dimension to understanding war propaganda both a century ago and today.

The translation is generally presented as is. Exceptions include using the full names where they were omitted in the original and providing editorial notes for context. As always, translation is an art, not a science. For instance, in some cases, I translated the word “power” (vlast‘)—in reference to those who ruled during the Civil War—as a “regime” because the author did not use the term “government,” and this translation is more in line with the theme.

The Story of a Life (Excerpt)

Konstantin Paustovsky

1962

The regime of the Ukrainian Directorate and Symon Petliura looked provincial. The once-brilliant Kiev turned into an enlarged Shpola or Mirgorod with their formulaic presences and Dovgochkhuns (Ivan Dovgochkhun is a character in How the Two Ivans Quarrelled (1834) by Nikolai Gogol – Ed.) who presided in them.

Everything in the city was designed to look like old-world Ukraine right down to the outdoor gingerbread stand featuring the sign “Oh, This is Taras from Poltava”. The long-mustached Taras was so pompous, and he wore such a snow-white shirt that bulged and blazed with bright embroidery, that not everyone dared to buy zhamki (thin gingerbread – Ed.) and honey from this opera character.

It was unclear whether something serious was actually taking place, or whether it was a play with the characters from Haydamaki (Taras Shevchenko’s 1841 poem – Ed.) that was unfolding. It was impossible to determine what was really going on. The time was spasming and bursting; the coups d’état came in waves. Each time a new regime emerged, clear and formidable signs of its imminent and pathetic collapse arose in the very first days.

Each regime hurried to announce even more declarations and decrees hoping that at least something out of these declarations would seep into everyday life and get stuck in it.

The reign of Petliura—just like hetman Pavel Skoropadsky’s reign—left a feeling of complete uncertainty about the future along with unclear thinking. Above all, Petliura looked to the French who, at that time, occupied Odessa. Soviet troops loomed inexorably from the north.

The Petliurites disseminated rumors that the French were already on the way to rescue Kiev, that they were already in Vinnitsa, in Fastov, and that the gallant French Zouaves (light infantry regiments – Ed.) in red trousers and protective fezzes might even appear tomorrow in Boyarka just outside the city. Petliura’s bosom friend, the French consul Émile Henno, swore to this.

The newspapers—going mad from all the contradictory rumors—willingly printed all this nonsense, while almost everyone knew that the French were firmly sitting in Odessa in their French occupation zone, and that the “zones of influence” in the city (French, Greek, and Ukrainian) were simply separated from each other with rickety Viennese chairs.

Rumors under Petliura took on the traits of a spontaneous, almost cosmic phenomenon similar to a pestilence. This was total hypnosis.

These rumors lost their direct purpose of reporting fictitious “facts.” Instead, such rumors acquired a new essence as if they were made of another substance. They turned into a means of self-soothing, or a powerful narcotic medicine. Only in rumors, people found hope for the future.

Even outwardly, Kiev residents began to resemble morphine addicts. With each new rumor, their typically cloudy eyes lit up, their usual lethargy disappeared, and their speech transformed from awkward to lively and even witty.

There were both fleeting and long-lasting rumors. They kept people in a state of deceptive excitement for two or three days.

Supporting my work allows me to bring you content on a regular basis.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

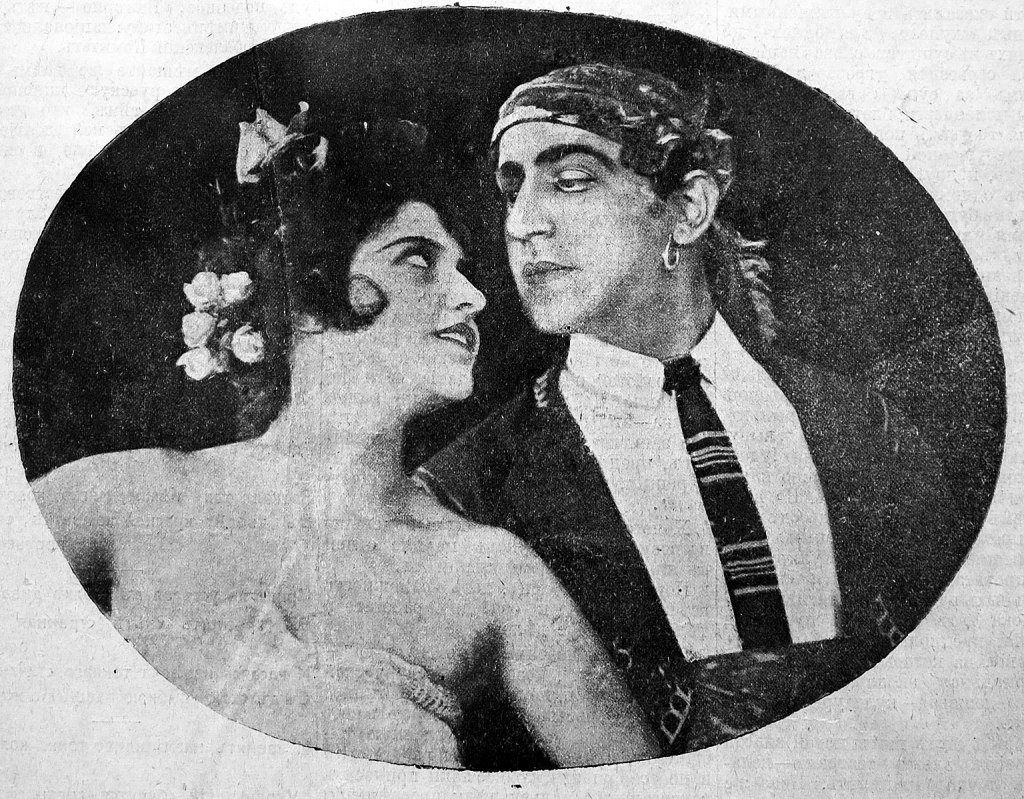

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyEven the most seasoned skeptics believed everything up to the point that Ukraine would be declared one of the administrative departments of France, and that Raymond Poincaré himself was on the way to Kiev to solemnly proclaim this state act, or that the film actress Vera Kholodnaya gathered her army and—akin to Joan of Arc—entered the town of Priluki on a white horse leading her reckless army where she declared herself the Empress of Ukraine.

At one point, I wrote down all these rumors but then stopped. I either got a terrible headache or felt quiet rage from this endeavor. As a result, I wanted to destroy everyone starting with Poincaré and President Woodrow Wilson and ending with “Father” Nestor Makhno and the famous Cossack ataman Zeleny (or Zeliony, the “Green Ataman” – Ed.) who ruled from the village of Tripolye near Kiev.

Unfortunately, I destroyed these notes. In essence, this was monstrous apocrypha of lies and uncontrollable fantasies of people who were helpless and confused. In order to recover a little, I re-read my favorite books that were transparent and warmed by unfading light: Ivan Turgenev’s Torrents of Spring, Boris Zaitsev’s The Light Blue Star, Tristan and Isolde, and Antoine François Prévost’s Manon Lescaut. These books truly shone in the dusk of hazy Kiev evenings like imperishable stars.